OUR NATIONS HIGHEST HONOR

IS BESTOWED UPON

William “Billy” Dixon

CHRISTMAS EVE 1874

FOR GALLANTRY IN ACTION

AT

THE BATTLE OF BUFFALO WALLOW

“I deem it but a duty to brave men and faithful soldiers to bring to the notice of the highest authority, an instance of indomitable courage, skill, and true heroism on the part of a detachment from this command, with the request that the actors may be rewarded, and their faithfulness and bravery recognized, by pension, medals of Honor, or in such a way as may bee deemed most fitting.”

Colonel Nelson A Miles, September 24th, 1874

Soon after the Battle of Adobe Walls, on August 6th, 1874, Billy Dixon signed on with Colonel Nelsons Miles’ Fifth Infantry as a Civilian Scout. He and another Scout, Amos Chapman and a detachment of four enlisted men were assigned to carry dispatches to Camp Supply, concerning the delay of the supplies being hauled by Lyman’s Wagon Train. Unknown to these men, Lyman’s Wagon train had been besieged for several days by Kiowa and Comanche raiding parties. The Scouts and soldiers had the bad luck of encountering the band of Indians, who had just left the wagon train Battle. The Cavalry scouts were attacked out in the open expanse of prairie, with no cover. A fierce battle ensued; Pvt. Smith, holding the horses was the first to be wounded. Amos Chapman was shot in the leg. Leaving the wounded men, the soldiers fought their way to a depression where the buffalo would roll and cover themselves in dirt or mud, called a “wallow”. Using their knives and bare hands, they pushed up dirt all around the outer edge of the wallow, which offered a slim barrier of protection from bullets and arrows. During the Battle, while under heavy fire, Dixon was able to race to Amos and carry him to the relative protection of the Buffalo Wallow, saving Chapman’s life. Dixon and another soldier did the same for Pvt. Smith, bringing him into the relative safety of the wallow, where he died later that night. The next morning, Dixon left the wallow on foot to find help, and fortunately, found Captain Price’s detachment. Price offered little assistance, but did report the stranded soldiers location to Colonel Miles, leading to the rescue of Dixon and his group.

After reporting on their fight to Colonel Miles, the Commander recommended all of them for the Medal of Honor. Mile is shown at right, during the Indian Campaign.

Until 1868, only three Medals of Honor had been awarded to participants in the Indian Wars. On Christmas Eve, 1874, Colonel Nelson A. Miles insisted he personally pin our Nation’s highest Honor on Billy Dixon. Dixon said “With his own hands he pinned mine on my coat when we were in camp on Carson Creek, five or six miles west of the original ruins of Adobe Walls.” The Colonel must have been very impressed with young Dixon’s capabilities as a Government Scout, as he also presented a personal letter to Dixon. This letter was very dear to Billy, as he kept it his whole life. The text of it may be read here.

All six participants of the Battle, Scouts Billy Dixon and Amos Chapman, and four enlisted men: Sgt. Z. T. Woodhall and privates Peter Rath, John Harrington, and George W. Smith, we also awarded Medals of Honor. Private Smith’s being awarded posthumously. Read our page about the Battle of Buffalo Wallow here.

THE 1916 MEDAL OF HONOR REVIEW BOARD

The Medal of Honor was created during the Civil War to recognize the heroic service of Military personnel, and remained the only Medal for Exemplary service until World War One.

In 1916, among concerns that too many Medals of Honor had been given for unwarranted actions, and with the understanding the Twentieth Century Medal of Honor was different than the Civil War medal, Congress ordered the Army to create a review Board of five retired Generals.

The Generals, coincidentally led by General Nelson Miles, at right, a forty two year veteran of the Army were tasked with reviewing every Medal of Honor awarded since the Civil War. General Miles’ Medal of Honor is the first Medal on the left, Awarded for Heroism after the Civil War battle of Chancellorsville.

The Generals directive was stated:

“Said board shall find and report that said medal was issued for any cause other than that herein before specified the name of the recipient of the medal so issued shall be stricken permanently from the official Medal of Honor list. It shall be a misdemeanor for him to wear or publicly display such medal, and, if he shall be in the Army, he shall be required to return said medal to the War Department for cancellation.”

They began their work in 1916, and finished eight months later.

To their credit, the board had removed the names from all the Medals and assigned them a number. Where they could, supporting documentation was reviewed. This board of Generals were very careful in their reviews, and cautious about rescinding anyone’s medal, as witnessed by this statement made at the time:

“The rewards which these men received were greater than would now be given for the same acts… the board has felt bound to measure the act by the standard established by the authorities at the time of the award, rather than by that now observed, thus avoiding…retroactive judgement.”

Eventually, after examining 2,625 Medals, the board revoked 911 of them. The majority rescinded were from two distinct Civil War groups: 864 from the 27th Maine Infantry and 29 Medals from the Soldiers that accompanied President Lincoln’s funeral guard- Soldiers that ceremoniously protected Lincoln’s remains as they toured the country. Additionally, the board decided to rescind the Medal from the first female Civilian surgeon ever employed by the Army. Dr. Mary Walker served with distinction during several Civil War battles, until being captured by Confederate Army soldiers and spending four months in a prisoner of war camp. Dr. Walker declined to return her Medal of Honor, and wore it publicly the rest of her life. Her Medal of Honor was reinstated in 1977.

The board reluctantly rescinded five Medals awarded to Civilians, as they were bound by Medal of Honor rules that state the Medal may be awarded only to enlisted men or officers of the Military. All five were civilian scouts for the Army. they included William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, Amos Chapman, William “Billy” Dixon, James Dozier, and William Woodall.

The Army didn’t want to make things worse for the recipients, so it never actually asked them to return the Medals. As you might imagine, those hearty souls capable of such acts of valor were understandably shocked to be told they didn’t deserve the medals. One might guess that they also weren’t keen about their return. By 1917, when the Board rescinded the Medals, Billy Dixon was deceased. He had strongly expressed his conviction to his wife Olive that he had earned his Medal of Honor. Olive simply didn’t return the Medal, and eventually donated it to the Panhandle-Plains Museum in Canyon. It is displayed with the original letter to Dixon from Miles.

Decades later, in 1989, these Medals of Honor were reinstated, and all of these men are now enshrined on the official Medal of Honor Roll.

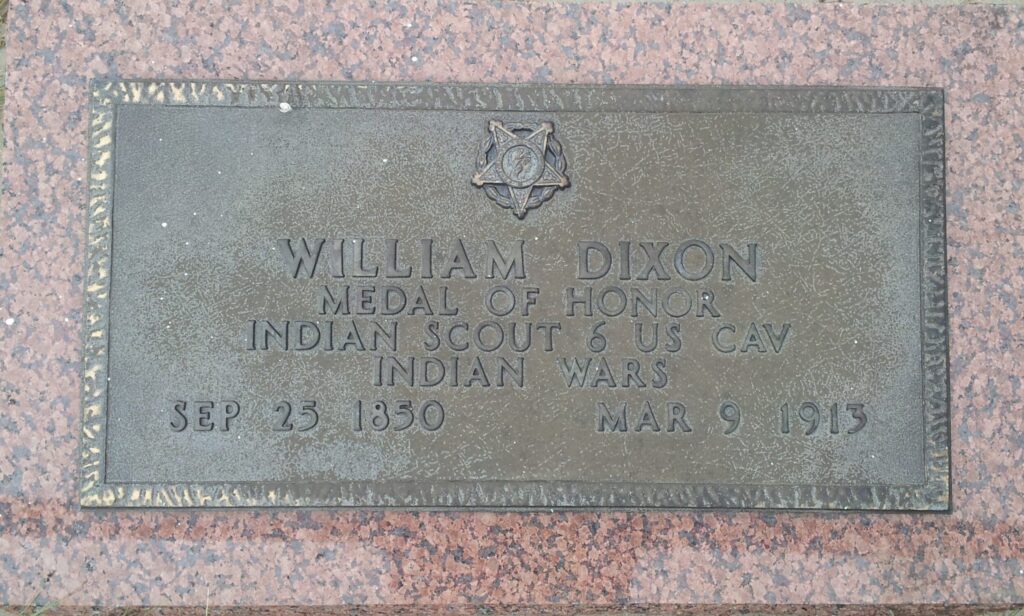

In 1992 this Medal of Honor marker was added to Billy Dixon’s Grave site

at Adobe Walls